Podcast here: https://soundcloud.com/user-280580802/213-the-threat-to-the-german-economic-model

The German economy is struggling and this brings a lot of unrest and public criticism against the three-party coalition government consisting of the Social Democrats (SPD), Liberals (FDP) and Greens. In the latest sign of discontent, farmers have been protesting against the budget amendment that would scrap fuel subsidies for farmers, which would substantially harm the small farmers. Big farmers could benefit as small farmers struggle to keep their business going and have to sell their farms to the big farmers. The budget amendment came after the German constitutional court prohibited the government’s budget practice of using unused debt from pandemic-era measures to fund certain climate change policies. Germany’s economic problems are significantly bigger than the budget laws and farmer unrest.

German industrial production has been declining for the last two years. Clearly, the pandemic can no longer be blamed for the declining industrial activity because most industrial production (except transportation equipment) has recovered in the second half of 2020. Since the beginning of 2022, most industrial production declined, except for electronics.

Source: https://twitter.com/heimbergecon/status/1745327536488276234

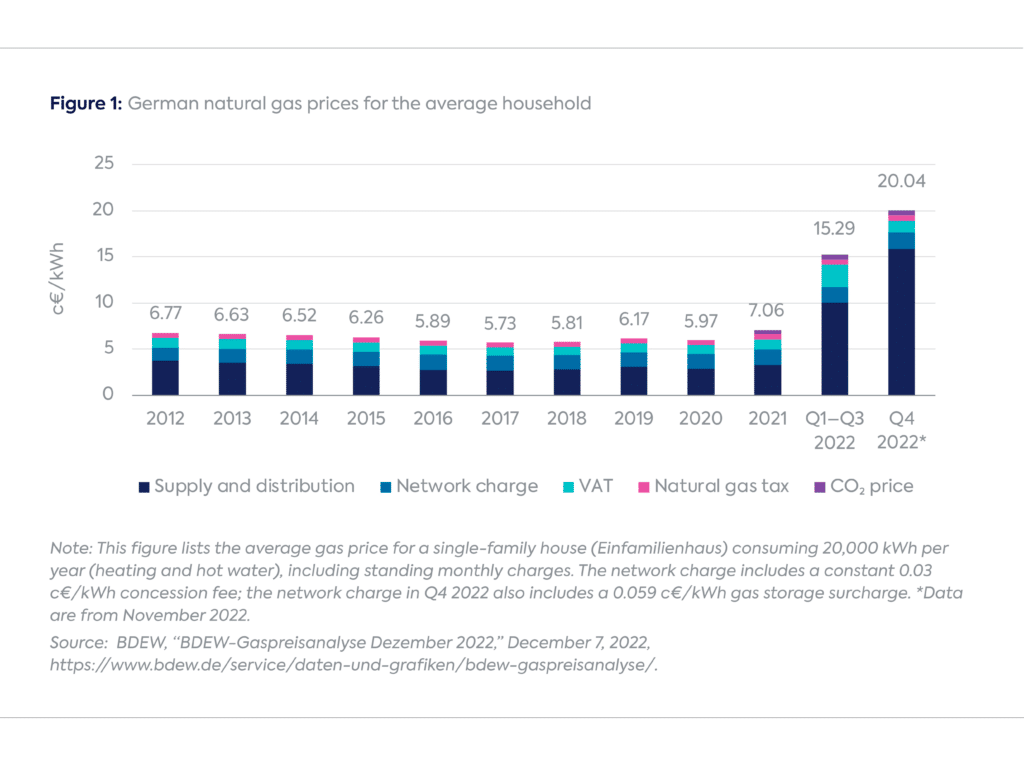

An important factor behind the declining industrial production is the increase in natural gas prices, which has effectively tripled by the end of 2022, reaching 20 euros. As of December 2023, that figure dropped again to 12 euros, lower than during the peak, but still much higher than before.

The rise in the gas prices can be explained by the Ukraine War and Germany’s heavy reliance on Russian natural gas. Germany has been importing Soviet gas since the 1970s and further pipelines over the Baltic Sea were added in the early-2010s (Nord Stream 1) and again before the start of the Ukraine War in 2022 (Nord Stream 2). With the start of the war these pipelines were shut down, and Germany promptly signed new LNG deals with the US, Norway and Qatar. It also built LNG terminals in northern Germany bypassing all of the previous environmental objections that had previously hindered its adoption. But the shipped gas is much more expensive than the Russian pipeline gas, hence the higher gas prices. The Nordstream pipeline was blown and no one wants to admit that they were responsible for it. Was it the US or Ukraine? Or was it Russia itself? A Washington Post article points to a Ukrainian special operator as culprit (Harris and Khurshudyan 2023).

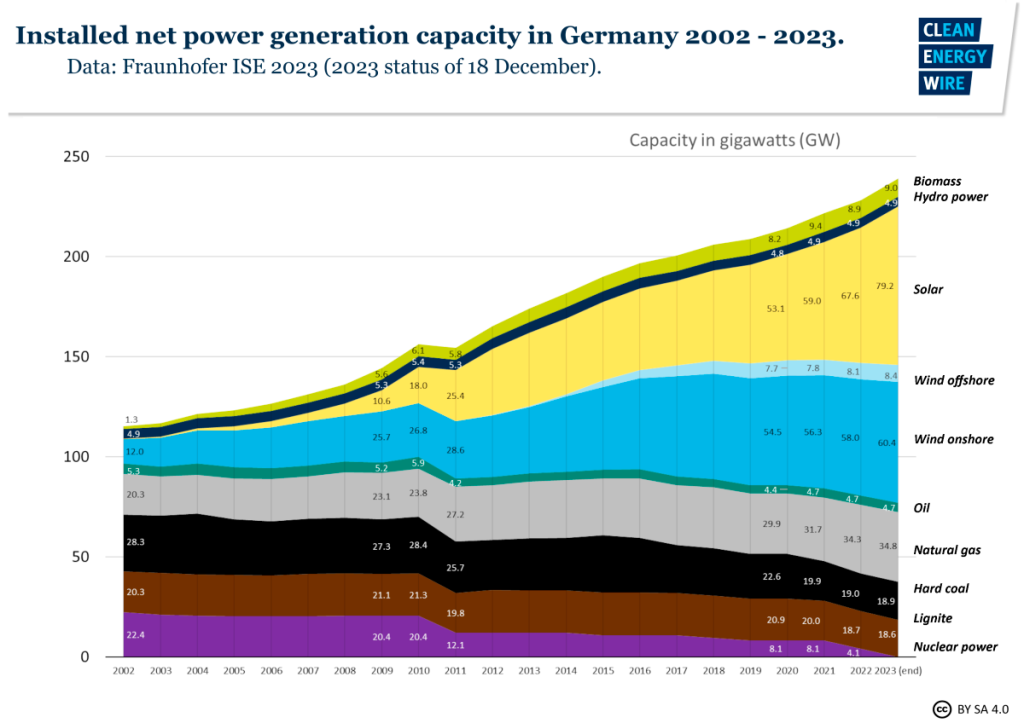

The Green Party had joined the coalition government in 2021 and has committed itself to a rapid green energy transition. The Green Party was merely accelerating an energy trend that has been happening over the last 15 years. German energy production has increased by 66% between 2010 and the end of 2023, but coal, lignite and oil consumption have been decreasing. Small increases come from biomass (essentially wood) and natural gas (hence the vulnerability to geopolitics). By far, the largest increases come from solar and wind. The renewable energy share has hit 50% with an 80% target by 2030.

Source: https://www.cleanenergywire.org/factsheets/germanys-energy-consumption-and-power-mix-charts

The renewable energy transition is to be welcomed given the continuously escalating global atmospheric temperature following our fossil fuel-based lifestyle. But it is questionable whether this can be done so swiftly, especially as geopolitical conflict are causing a rise in energy prices that are followed by social unrest. Climate policies must be viewed as legitimate in order to work. Economy minister Robert Habeck’s decision to phase out nuclear energy despite the three nuclear plants still operating at the beginning of the Ukraine War shows the lack of prudence in the German government. Consider also that the Gerhard Schroder government had made the fateful decision to shut down the nuclear plants and rely on Russian gas while transitioning to renewable energy. Habeck still has to be commended for eating his environmental hat and agreeing to sign the LNG contracts with Qatar. He cared more about raison d’etat than green ideology.

Given the decline of industrial production and the heavy reliance on manufacturing as a share of the economy (about 18%), Germany cannot fully rely on renewable energy to operate manufacturing. Some renewable energy sources like hydrogen are still very experimental, and hence expensive to produce. 67% of German businesses have moved some of their operations overseas, resulting in deindustrialization (Caddle 2023). Popular locations are other EU countries or US and Canada that have their own (cheaper) gas supplies.

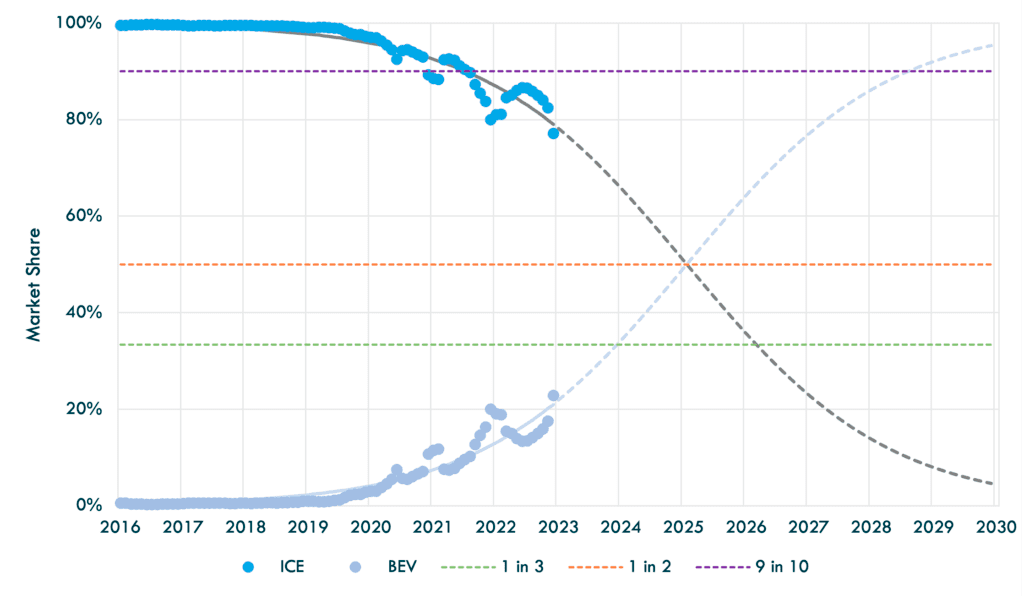

Energy prices are not the only challenge for German industry. Volkswagen has been the leading car producer in the world specializing in ever more fuel efficient combustion engine cars. Consider that Gottlieb Daimler, Karl Benz and Nicolaus Otto, all Germans, were the first people to have developed the commercial combustion engine vehicle in the 1880s. They have this age-old technology and believe that it will be in use for eternity. But as there are more and more electric vehicles from the US (Tesla) and China (BYD, NIO etc.) flooding the world market, the Germans are expected to lose car market share in the years ahead unless they aggressively join the EV movement. I am still somewhat skeptical of EVs because of short battery lives and the inconvenience of long charging times. However, EVs are less complex and have fewer parts than combustion engine cars. The business-friendly FDP has been bullish on e-fuels and is pushing the EU to add an exemption for e-fuels to the 2035 phase-out of combustion engine vehicle sales. It’s still very expensive to produce and cannot scale as of now (Posaner 2023).

Combustion engine (ICE) and Electric engines (BEV) market share, Source: https://earthbound.report/2023/01/12/tracking-the-decline-of-the-combustion-engine/

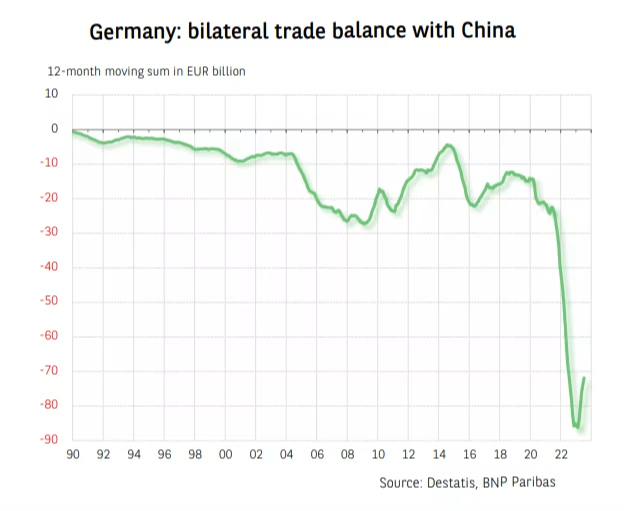

Germany’s export economy is threatened by the poor economy of its biggest trading partner China (McHugh 2023). China faces a rapidly shrinking fertility rate/ population. In China, the real estate sector is over-inflated, the corporate debt is very high, US sanctions are biting, capital is fleeing overseas. 10% of Germany’s GDP is exclusively the export of goods and services to China (The Economist 2023). On the other hand, the slightly negative trade deficit with China which was less than 20 billion euros spiked to over 80 billion euros in 2022 (Barber 2024). Exports to China peaked in early-2021 at around 12 billion USD a month and declined to less than 8 billion euros as of October 2023 (CEIC). Rising imports from China are focused on the electrical equipment sector where German companies are rapidly losing competitiveness (Colliac 2023). In the meantime, the German government and especially the Green Party foreign minister Annalena Baerbock is increasingly harping on a China-unfriendly position and falling in line with the hawkish US position. Baerbock took a course in international law and focused on human rights, which makes her naturally hostile to authoritarian regimes like the ones in Russia or China. It is questionable whether the biggest German trading partner can be snubbed so easily.

Source: https://www.ft.com/content/2e83bd08-90c4-467a-86a4-4db2e31d60de

Deindustrialization has been an ongoing phenomenon across many developed countries. In the German context, the city of Essen in Ruhr region of North Rhine Westphalia is a good case study for the impact of the loss of coal mining and steel-making that was essential for German industrialization from the late nineteenth century onward. Coal extraction in Essen had peaked in 1957 and has been declining ever since. German energy coal dependence decreased from 72% to 13% from 1950 to 2000. Many coal mines closed between 1960 and 1980 leaving many residents unemployed or displaced into less lucrative service industry jobs. The government has been trying to restore the economy over the years such as investing in the arts, the hydrogen industry (Chen 2023).

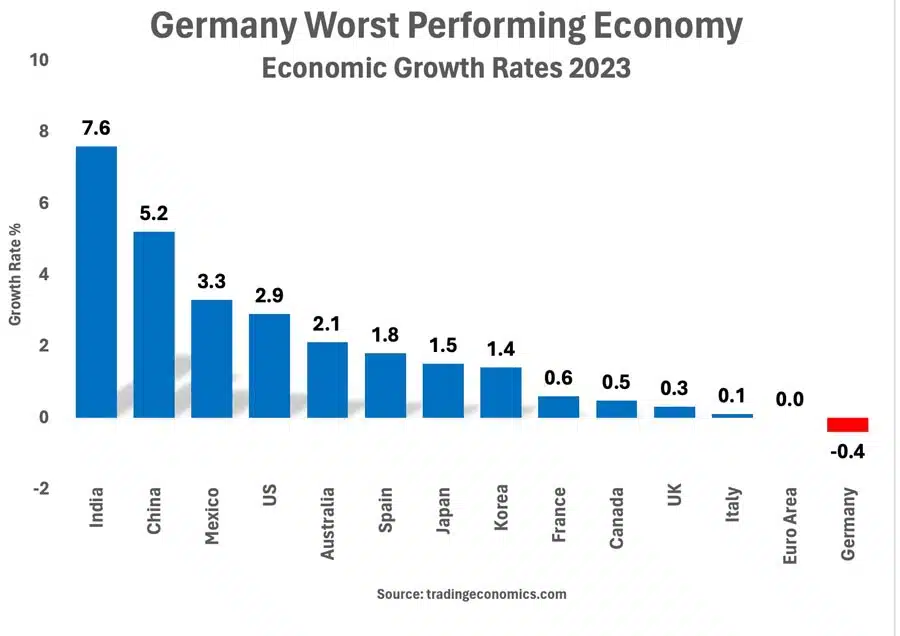

Deindustrialization has already negatively affected the overall economy. It is the worst performer among the large economies, having shrunk by 0.4%.

Source: https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/214905/economics/the-problems-facing-the-german-economy/

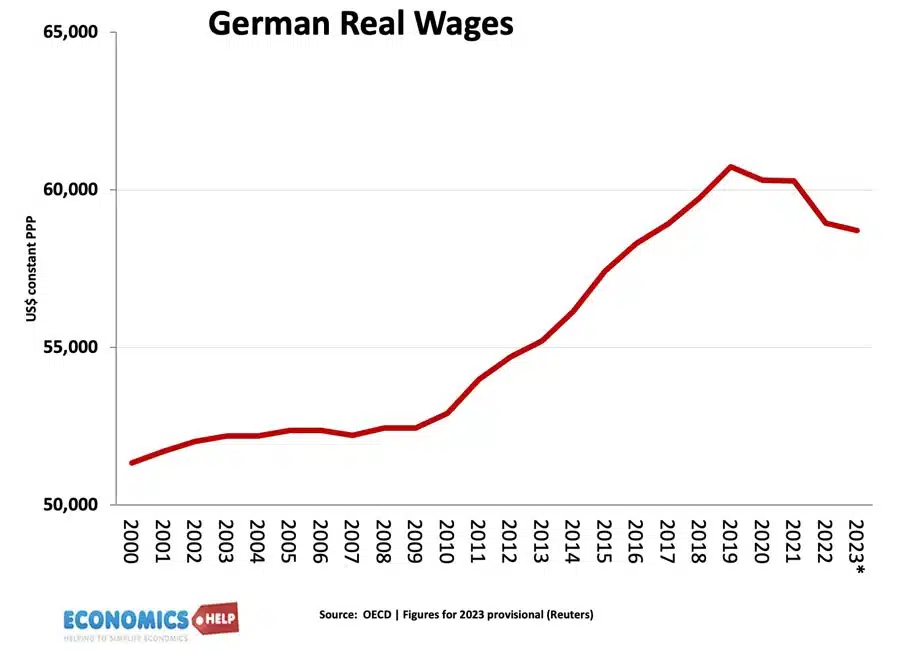

Deindustrialization also has negative consequences on real wages given that there are many workers in the manufacturing sector or are servicing that sector (think of car mechanics being laid off or have their pay cut shortly after car manufacturing workers following car sales declines). Real wages have peaked in 2019 and have declined by several thousand in inflation-adjusted terms. Labor strikes are happening in different industries, e.g. in the rail industry (Schuetze 2024). The rail industry is already quite unreliable given the lack of public investments resulting in frequent delays and long wait times for the trains. One third of all the trains arrived late in 2023, mainly due to construction work, labor strikes and poor weather (Berry 2024).

Source: https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/214905/economics/the-problems-facing-the-german-economy/

While wages have been lagging, unemployment is still quite low and there is a severe shortage of skilled labor due to the rapid aging of society, which also explains the government’s recent decision to allow foreign-descent persons to acquire dual citizenship and lower the length of residency to acquire citizenship from 8 to 5 years. Even with the slowing economy the unemployment rate remains below 6%. Sectors with a lot of job vacancies are transportation, logistics, social work, childcare, education, care for the elderly (Statista; Statista 2023).

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/227005/unemployment-rate-in-germany/

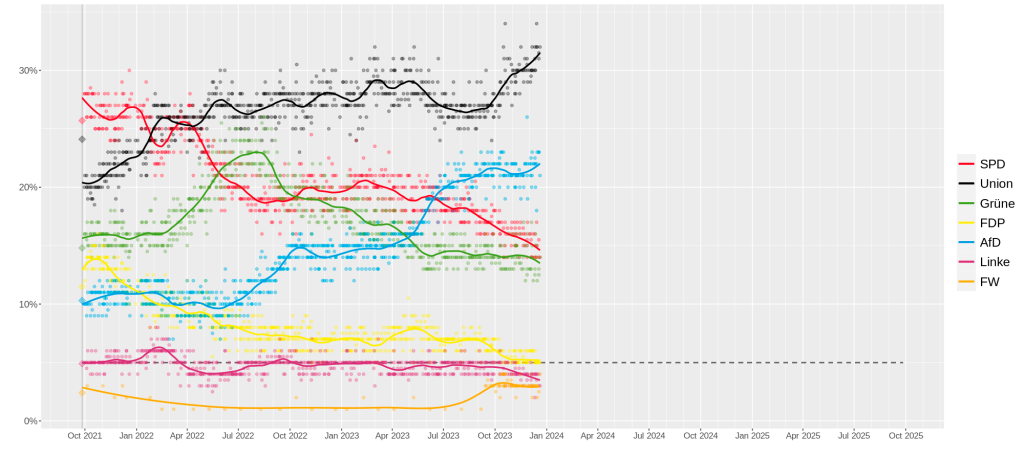

Given this worsening economic state, it is not surprising that popular support for the governing parties is declining, although the Greens, who have been castigated for their fast energy transition program, have held the line the best losing only 1 or 2 points in support. The environmentalists, who insist on the urgency of climate change, have nowhere else to go, while the climate has become even crazier. In contrast, the SPD has lost about half their voters from the last election and so does the FDP. There is a chance that the FDP will not make it into the parliament in the next legislative elections. Chancellor Olaf Scholz is a very risk-averse and uncommunicative leader, which is a leadership style that he attempted to copy from his unpretentious predecessor Merkel, who stayed in the chancellory for 16 years. It is questionable whether Scholz can replicate this long tenure.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opinion_polling_for_the_next_German_federal_election

Scholz had the bad luck of facing the Ukraine invasion two months after starting on the job. He began his tenure with grand promises to alleviate the housing shortage and build more wind turbines, but instead had to manage a massive rearmament program for the Bundeswehr (German army) and financial support to Ukraine and Ukrainian refugees entering Germany. While Germany keeps upping the financial and military aid to Ukraine, becoming its second-biggest backer behind the US, Ukraine complains that the help is never enough. For instance, the French and British are delivering cruise missiles, which the Germans, and especially chancellor Scholz, refuse to do. With the US MAGA faction choking off Ukraine funding, Ukraine’s reliance on German support is only growing. Scholz is also overseeing high inflation and less industrial activity. Instead of driving social democratic policy, he is moderating the tension among his coalition partners, one of which wants to spend very little tax money on climate or social programs (led by finance minister Christian Lindner) and the other wants to do more on both (led by vice chancellor Robert Habeck) (Kinkartz 2023).

The two main beneficiaries of the government’s unpopularity are the conservative CDU/CSU (Union) and the right-wing nationalist AfD. It is noteworthy that while the three governing parties are running against the AfD rhetorically, rejecting their neo-Nazi messaging, the CDU is only against the AfD leadership but does not want to demonize its voters. Firstly, CDU leader Friedrich Merz is closer to the right-wing of the CDU than his predecessor Angela Merkel was. Secondly, CDU knows that the reason why their polling value is not even higher is because of the competition for votes with AfD. The right-wing conservatives that are interested in migration limits, the preservation of a German Christian culture and traditional family/ gender norms have usually voted for the Union parties, and that was still the case during the Merkel era, even though she was somewhat more liberal than many of her party members.

The AfD was founded in 2012 initially as a technocratic neoliberal party that wanted Germany to leave the eurozone and pursue more economic nationalism. But that technocratic message did not attract a significant amount of voter support and the party failed to enter parliament in 2013. In 2017, it entered the parliament, but this time new party leaders moved the party to the right on migration. 2015 was the year that many Syrian refugees fled to Germany, overwhelming the “Willkommenskultur” (welcoming culture) that the German political elites espoused during the early refugee wave, thus polarizing the migration topic and fanning the support for the AfD. With the Covid crisis, Ukraine war (including its many refugees), rising inflation and now deindustrialization, there are more and more areas where the political elites lack the tools to master these crises.

AfD support mixes anti-establishment sentiment due to incompetent political elites unable to solve their problems or making them worse with “volkisch”/ racist nationalism. The latter is about hurling the country back to a mythical past where everyone was white and the economy was booming. It is a non-working recipe. Consider, for instance, demography: Less than 80% of the German population is of native stock, and native German women’s fertility rate is about 1.4 compared to the 1.9 of the foreign-descent women. Where is the mythical past the AfD wants to go back to? The society can scarcely function without the many foreigners and Germans of foreign descent. Surely, there are more integration issues for war refugees from Africa and Middle East without German language background going to Germany compared to the high-skilled English-speaking migrants going to the US, UK or Canada. Can all of the refugees fill precisely the jobs where there are a lot of openings? It’s unlikely at least in the short term.

There is a lot of dissatisfaction with the AfD too as the many anti-AfD protests show. Even the Nazis never gained more than a third of the popular vote, while the ones that didn’t vote for them detested them. Drawing parallels with the 1930s is not so simple because German society is substantially more diverse today than it was back then. But one root cause of the rise of Nazism is the sharp decline of the middle class, which could very well be a structural trend given the lack of energy security, the high cost of the energy transition, the high cost of sustaining the war effort in Ukraine, the continuing deindustrialization, or the slow pace of innovation.

Despite these challenges, Germany also has a lot of advantages with its economic institutions, including the training institutes, apprenticeships and great universities, the large number of small and medium-sized businesses, the high level of human capital, and the liberal democratic culture. A thriving Germany is essential for a strong united Europe that is facing more geopolitical headwinds due to a potential Trump presidency abandoning the NATO alliance, the Russians threatening Europe’s eastern flank and the Global South countries (especially India and China) taking more market share from the old industrial powers. Let’s hope that the “sick man of Europe” (Germany’s designation in the late-1990s) becomes healthy again without doing it at the cost of other European countries, as was the case with its mercantilist policies among deficit-generating Eurozone countries in the early-2000s.